Civilians, including children, killed and injured in armed conflict

(YANGON, June 4, 2019)— The Government of Myanmar and the Arakan Army (AA) should protect civilians trapped in areas of armed conflict in Rakhine State and urgently ensure humanitarian access to affected communities, said Fortify Rights today. On May 20, at least two Rohingya civilians were shot in Kyauktaw Township during fighting between the Myanmar Army and the AA, and on May 21, a 35-year-old Rohingya man and his eight-year-old son died from injuries caused by an explosion from an undetermined source.

Fortify Rights also received credible reports of Myanmar Army soldiers killing, torturing, and arbitrarily arresting Rakhine civilians since January 2019—violations that would amount to war crimes. Rakhine also self-identify as Arakanese or Arakan.

“State security forces continue to act with complete impunity in Rakhine State,” said Matthew Smith, Chief Executive Officer of Fortify Rights. “The government must urgently ensure aid reaches all those in need and the international community should step up efforts to hold perpetrators accountable.”

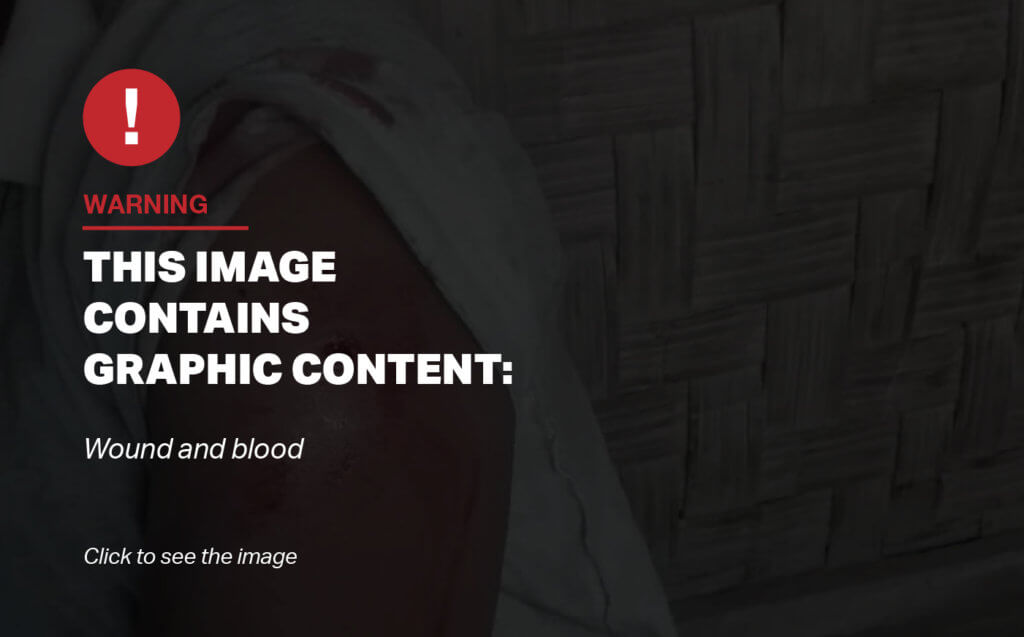

Fortify Rights spoke with eight Rohingya civilians in Ah Lel Kyun village in Kyauktaw Township, Myauk U District, Rakhine State, the site of heavy fighting between the Myanmar Army and AA on May 20 and 21. Among those interviewed were a 35-year-old woman who was shot in the back, a 16-year-old boy injured by shrapnel, and a local aid worker who treated two Rohingya adults who were shot and two Rohingya children who sustained other injuries. Six Rohingya eyewitnesses and survivors in Ah Lel Kyun village described mortar shelling, gunfire, and explosions as well as the visible presence of Myanmar Army soldiers.

Fortify Rights was unable to confirm who was responsible for the casualties.

A local health worker, 38, who treated Rohingya civilians injured by the fighting on May 20, told Fortify Rights:

I treated four injured people. Two kids, one woman, and one man . . . all Rohingya people. The man and the woman had bullets [in their bodies]. The man had a bullet in his arm. The woman had a bullet in her back. And the two kids were bleeding and injured but had no bullet wounds.

The nearest hospital is in downtown Kyauktaw; however, injured Rohingya civilians are unable to access medical care outside their village due to the government’s longstanding restrictions on freedom of movement against Rohingya.

“[The Rohingya] need a form-four application to travel, but getting permission to travel can take time,” said the local health worker to Fortify Rights. “And many Rohingya patients and injured people die while waiting for approval.”

“We need access—predictable, sustained access—to reach the people in need [in Rakhine State],” Ursula Mueller, a U.N. assistant secretary-general for humanitarian affairs told Reuters on May 14.

There are an estimated 598,000 Rohingya still living in Rakhine State, many of whom are confined to their villages or internment camps and in need of humanitarian aid.

There are seven hamlets in Ah Lel Kyun village, three of which comprise predominantly Rohingya residents and four of which are home to predominantly Rakhine residents. Altogether, the population of residents living in the three Rohingya hamlets is approximately 3,800.

“Myanmar authorities need to urgently ensure all civilians trapped and affected by this conflict are protected and have access to emergency medical care,” said Matthew Smith. “The government continues to deny Rohingya freedom of movement, and in a situation like this, that’s deliberately destructive.”

On May 21, around 11 a.m., an explosion in Ah Lel Kyun village killed a Rohingya man, 35, and his eight-year-old son. Fortify Rights received photographs and video footage of the victims’ bodies matching descriptions from eyewitnesses. Based on eyewitness testimony and photographic evidence, Fortify Rights was unable to confirm if the explosion was from a landmine, an improvised explosive device, or unexploded ordnance.

Fortify Rights spoke to two eyewitnesses to the explosion and two who witnessed the immediate aftermath, including a family member of the deceased, who told Fortify Rights:

Both legs of [the man] were injured. I wanted to take [him] to the hospital but I couldn’t go to the hospital because it’s in a Rakhine village and there are [military] checkpoints. [The boy] died after five minutes of being hurt by the fighting . . . He was hurt in the stomach. His stomach exploded.

A Rohingya boy, 16, was wounded from the same explosion and described being hit by shrapnel while nearby. He told Fortify Rights: “Something hit my leg. I can’t walk, it’s very painful . . . The Myanmar military comes to our village. They walk along the road. They sometimes beat people . . . I cannot [regularly] go to school. The fighting has been ongoing.”

Another Rohingya man, 38, told Fortify Rights about the explosion on May 21:

The boy brought the bomb in from the farmland and it exploded in the village [on May 21]. . . On May 20, when they shot at the village, the bomb didn’t explode. The boy didn’t know if it was a toy or a bomb and he brought it into the village. . . Maybe the man could have lived if he got treatment.

Residents described more than an hour of fighting between the Myanmar Army and AA in Ah Lel Kyun village on May 20, with one Rohingya eyewitness, 38, alleging “the [Myanmar] military fired through our village.”

He continued: “The Myanmar authorities are blocking Rohingya from traveling. They don’t treat Rohingya like humans. We can’t go anywhere or get treatment or education.”

Fortify Rights spoke with a Rohingya woman, 35, who was shot in the back on May 20 in Ah Lel Kyun. She said:

I was sleeping inside [when I was shot]. My roof was destroyed by firing. There were many [Myanmar Army] soldiers in the farmland. The hit on my back was from a bullet . . . It was not direct . . . I was not allowed to go to the hospital. The village health worker is treating me . . . at least seven people were injured in the village.

A local Rohingya resident, 32, from Ah Lel Kyun village told Fortify Rights that on May 20, the “Myanmar army started firing on our village.” He said he believed the Myanmar Army and the AA were both planting landmines in the vicinity of Ah Lel Kyun village: “We cannot deny they are planting landmines in our area. There are consequences, Rohingya are injured and killed. That’s our life now.”

On May 21, two Rakhine civilians aged 25 and 27 reportedly suffered injuries after they stepped on a landmine in Nga Pyaw Chaung village in Kyauktaw Township. They were treated at a local hospital.

Clashes between the Myanmar Army and the AA occurred during U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi’s five-day visit to Myanmar. This was the first visit by the head of the U.N. Refugee Agency to Myanmar since August 2017.

The Development Media Group (DMG) reported on the fighting in Ah Lel Kyun village and other human rights violations in Rakhine State. On May 1, the Special Branch Police, operating under the Ministry of Home Affairs, filed charges against the Editor and Executive Director of DMG Aung Marm Oo, who is based in Rakhine State. On May 21, Fortify Rights called on the authorities to immediately drop the charges and to protect the right to freedom of expression.

The Myanmar military and AA have engaged in armed conflict since 2015. The AA formed in 2009. Clashes between the two armies displaced more than 30,000 civilians in seven townships of Rakhine State since January 2019. In 2016, Fortify Rights documented how the Myanmar Army forced Rakhine civilians to dig graves and carry supplies under the threat of death during fighting with the AA in Rakhine State.

Myanmar authorities–both military and civilian–are responsible for restrictions on the transport of aid in Rakhine State, including medical supplies in conflict-affected townships. On April 1, 16 international humanitarian organizations in Myanmar issued a statement saying that since January 10, “the Government of Myanmar has imposed restrictions on the access of humanitarian and development agencies in five key townships,” including Kyauktaw Township. “Health care services, education and access to clean water have all been jeopardized,” the organizations said.

The Government of Myanmar has a responsibility to protect civilians in situations of armed conflict. The authorities’ willful deprivation of humanitarian aid to civilians affected by armed conflict in Rakhine State violates international humanitarian and human rights law. Under international humanitarian law, or the laws of war, all parties to armed conflict are obligated to “facilitate the free passage of humanitarian assistance” and ensure aid workers have “rapid and unimpeded access” to civilians.

In July 2018, Fortify Rights published a 160-page report detailing how Myanmar authorities made “extensive and systematic preparations” for attacks against Rohingya civilians in Rakhine State in 2017 that constituted genocide and crimes against humanity. Fortify Rights named 22 military and police officials who should be investigated and possibly prosecuted for genocide and crimes against humanity.

In September 2018, the U.N. Fact-Finding Mission (FFM) on Myanmar released a 444-page report cataloging Myanmar military-led atrocity crimes against civilians and calling for the U.N. Security Council to refer the situation in Myanmar to the International Criminal Court (ICC) or to establish an ad hoc international criminal tribunal to investigate and prosecute senior Myanmar military and police officials for genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity against Rohingya, Kachin, Shan, and others.

On September 6, 2018, the ICC granted the Chief Prosecutor jurisdiction to investigate and possibly prosecute the crime against humanity of forced deportation of Rohingya to Bangladesh as well as persecution and other inhumane acts. On September 18, 2018, the U.N. Human Rights Council also created the Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar (IIMM) to collect and preserve evidence of crimes in Myanmar for future prosecution. The IIMM is expected to become operational after the FFM delivers its final report to the U.N. Human Rights Council in September.

“Accountability is urgently needed in Rakhine, Kachin, and Shan states, and it won’t come from Myanmar authorities,” said Matthew Smith. “The international community needs to use every available tool and step up efforts, which can help prevent the next round of mass atrocities.”