“LGBT rights are human rights. I want to encourage fellow LGBT people not to be discouraged”

By Sippachai Kunnuwong

(BANGKOK, August 2, 2022)—Since the February 1, 2021 coup d’état and the Myanmar military’s subsequent violent crackdown, anti-junta protesters continue to flee to the Myanmar-Thailand border to escape arbitrary arrest and other reprisals for their activities. Members of the LGBTI+ community are among the many displaced now living in uncertainty.

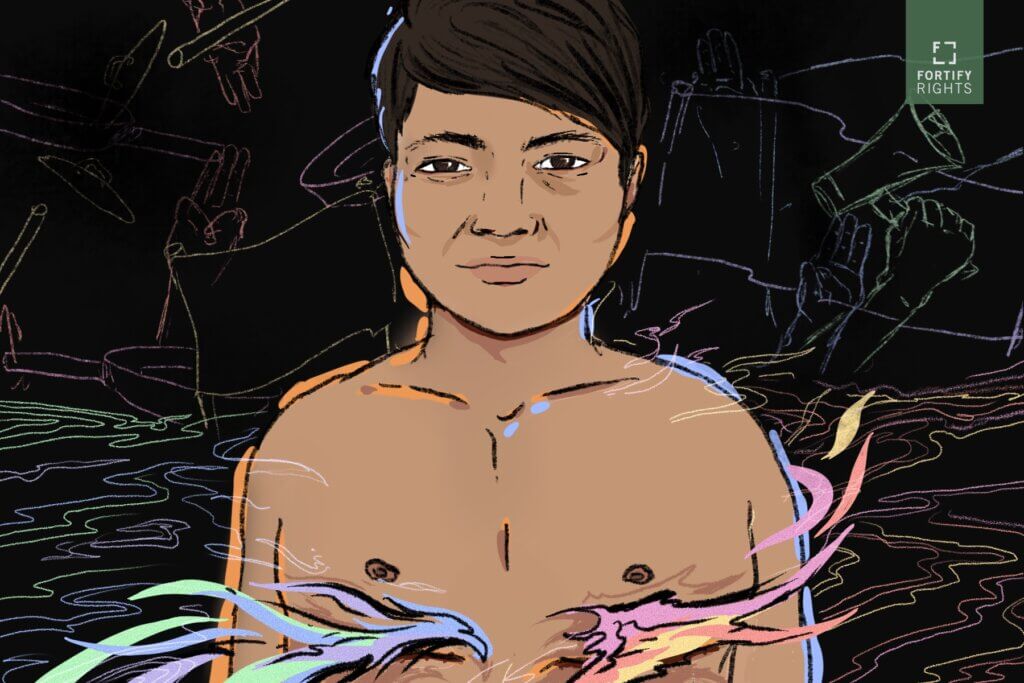

Proudly displaying a tattoo of bird wings covering two long lateral scars across his chest, Ray Sam, a Myanmar anti-junta activist, told Fortify Rights how he underwent gender-affirming “top” surgery to masculinize his chest just two days before the coup.

“The doctor told me to rest for more than one month [after the surgery to avoid] a bad scar,” Ray Sam said. “But I didn’t care. I couldn’t wait.”

Against his doctor’s advice, Ray Sam joined the street protests to oppose the coup.

“The damage [to the wounds] was huge,” he said. “My scars became very big. I covered it with a tattoo . . . I participated knowing the risks because I want freedom. I like democracy. I dislike military coups.”

“We had to leave his dead body there.”

On February 1, 2021, junta forces arrested and imprisoned Ray’s brother, a member of the National League for Democracy (NLD)—the political party led by Aung San Suu Kyi that won the 2020 general elections in a landslide victory.

Explaining his family’s longtime connections with and support for the NLD, he said, “During the 1990 general elections, my mom was campaigning for the NLD party while she was pregnant with me. We are brothers—the NLD and me. I joined the rallies since I was in the womb.”

When the 2021 anti-junta protests began following the coup, his entire family got involved. He said:

“Our involvement in the protests between February to March 3 [2021] led my family to be targeted by [the junta] . . . On March 3, my family led a demonstration, which started with 150 demonstrators. The crowd became bigger and grew to 500 . . . After the incident, we didn’t go back to our house. We became public figures because we led the demonstrations.”

In April 2021, Ray and his family went into hiding to avoid arrest. Shortly after, his father died of COVID-19.

“We couldn’t make a proper cremation for [my dad],” Ray recalled. “In the villages, whenever there was a funeral, people had to register the name of the deceased. But if we disclosed his name, the [junta] would know our whereabouts. We had to leave his dead body there. I couldn’t do anything.”

After his father died, Ray and his remaining family fled Myanmar. Explaining this decision, Ray Sam told Fortify Rights: “We didn’t plan to move out of our country. We loved our country. When my dad died, we had to move.”

“[My gender identity] was another push factor for me to move to [Thailand],” he continued. “There were cases of LGBTI+ protesters who were raped in detention. I didn’t have a sex change yet, so I was so terrified about that.”

“Now, I’m really proud of myself.”

Although Ray only recently underwent gender-affirming surgery, he has lived almost his entire life as a transman in Myanmar.

“I realized [I was trans] since Grade 5,” he told Fortify Rights. “I realized I didn’t like dressing like a girl. I borrowed my brother’s trousers and dressed as a boy,” he said, adding that he has kept his hair short since middle school.

Ray recalled the challenges he and his longtime partner, a Myanmar traditional dancer, faced in Myanmar:

Some of her colleagues would say: “Why can’t you find a real man? You are talented and beautiful.” But she really loves me and wants to be with me . . . Even after they accepted me, they still teased me . . . So, I’ve started accepting that there may be people who accept me and some who do not. But, sometimes, my feelings get hurt too.

Unable to legally marry in Myanmar, Ray and his partner have lived together as husband and wife since 2015. He explained how both their parents began to accept their relationship over time. He said:

In Burmese culture, the elders teach us about the responsibility we have when we get married. My mom asked if I could follow a husband’s duty. I said: “Okay. I can take the responsibility of a husband.” She then became okay with my transition as a man.

His partner’s family required more convincing. Explaining, he said:

I couldn’t have a good relationship with my girlfriend’s family. They live in a rural area, and the people there don’t have contact with someone like me, so they couldn’t accept my gender identity . . . They didn’t trust me because they thought I might get married to a man. But after the operation, my mother-in-law now calls me “son,” and she’s proud of me.

Explaining how this support gave him confidence, he said:

Before, I was shy to show my gender identity. I was really shy to stand or speak in front of people. I didn’t want to talk about my “tomboy” life. Now, I’m really proud of myself. If I have a “bottom” (sex reassignment) operation, I can advocate more for transmen.

“LGBTI people need targeted and psychological support.”

Ray Sam now supports and advocates for other members of the LGBTI+ community displaced by the coup.

Explaining the unique needs of LGBTI+ refugees, he said:

LGBTI people need targeted and psychological support. Some LGBTI people don’t have friends who accept them for who they are. They may feel discouraged about their reality. They may feel like they can get less support than other people. I always tell them: “No, you can get this and that. You can get equal support.”